NetPlay

Overview

Recently, Large Language Models (LLMs) have shown great success as high-level planners for game-playing agents. However, many of these agents are primarily evaluated in simple environments with few objects or interactions

We introduce NetPlay, the first LLM-powered zero-shot agent for the challenging roguelike NetHack

NetPlay excels in executing detailed instructions but struggles with more ambiguous tasks, such as winning the game. We discovered that NetPlay’s strength lies in its flexibility and creativity. Our experiments show that given enough context information, NetPlay can perform a wide range of tasks. Moreover, by focusing its attention on a particular problem, NetPlay is adept at exploring a wide range of potential solutions, but often with limited success due to a lack of explicit feedback guiding it.

What is NetHack?

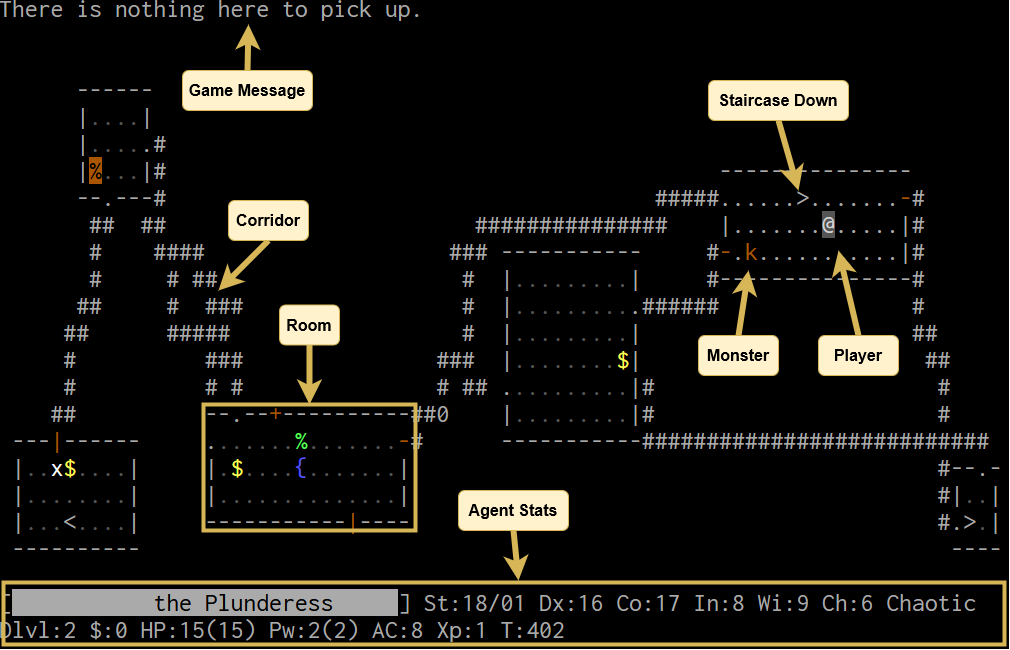

NetHack

NetHack encompasses a diverse array of monsters, items, and interactions. Players must skillfully utilize their resources while avoiding many of the game’s lethal threats. Even for seasoned players possessing extensive knowledge of the game, victory is far from guaranteed. The game’s inherent complexity requires players to continuously re-assess their situation to adapt to the unpredictability of the elements at play.

The sheer size of NetHack, paired with the many sub-systems the player must understand, makes it an excellent candidate for evaluating the limitations of LLM agents. We used the NetHack Learning Environment

NetPlay

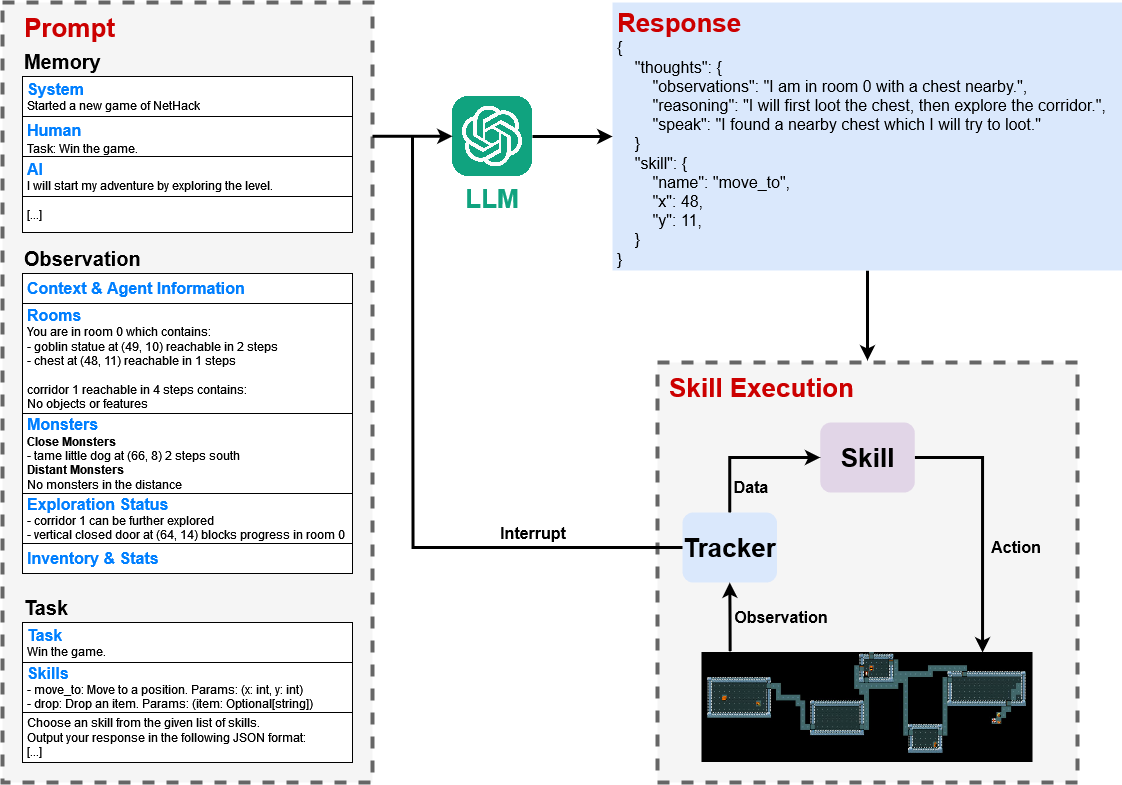

Long-term planning in NetHack proves challenging due to its unpredictability, as we cannot know when, where, or what will appear as we explore. Consequently, our agent implements a closed-loop system where the LLM selects skills sequentially while accumulating feedback through game messages, errors, and manually detected events. Although we avoid constructing entire plans, the LLM’s thoughts are included for future prompts, allowing for strategic planning if deemed necessary by the LLM.

Prompting

We prompt the LLM to choose a skill from a predefined list. The prompt comprises three components: (a) the agent’s short-term memory, (b) a description of the observation, and (c) a task description alongside the output format.

(a) The observation description primarily focuses on the current level alongside additional data like context, inventory, and the agent’s stats. We attempt to convey spatial information by dividing the level into structures like rooms and corridors. Monsters are described separately from the structures by categorizing them as close or distant, indicating their potential threat level. The LLM is also informed about which structures can be further explored alongside the positions of boulders and doors that block exploration progress.

(b) The short-term memory is implemented using a list of messages representing the timeline of events. Each message is either categorized as system, AI, or human. System messages convey feedback from the environment, such as game messages or errors. AI messages are used for the LLM’s responses. Human messages indicate new tasks. Note that while it is possible for a human to provide continual feedback, we only study the case where the agent is given a task at the start of the game.

(c) The task description includes details about the current task, available skills, and a JSON output format. We employ chain-of-thought prompting

Skills

| Name | Parameters | Description |

|---|---|---|

| explore_level | Explores the level to find new rooms. | |

| press_key | key: string | Presses the given letter. |

| pickup | x: int, y: int | Pickup things. |

| up | x: int, y: int | Go up a staircase. |

| drop | item_letter: string | Drop an item. |

| wield | item_letter: string | Wield a weapon. |

| kick | x: int, y: int | Kick something. |

| cast | Opens your spellbook to cast a spell. | |

| pay | Pay your shopping bill. |

NetPlay uses handcrafted skills that implement different behaviors by returning a sequence of actions. They accept both mandatory and optional parameters as input. Skills can also generate messages as feedback, which are stored in the agent’s memory.

Navigation is automated through skills like move_to x y or go_to room_id. However, exploring levels with only these skills proved challenging for the LLM. To address this, we automated exploration with the

To indicate when the agent is done with a given task, it has access to the finish_task skill. Additionally, the LLM is equipped with the press_key and type_text skills for navigating NetHack’s various game menus.

The remaining skills are thin wrappers around NetHack commands, such as drink or pickup. However, these commands often involve multiple steps, such as confirming which item to drink or positioning the agent correctly to pick up an item. Consequently, the LLM often assumed that the drink command accepts an item parameter or that pickup works seamlessly regardless of the agent’s current position. To mitigate these issues, most command-skills automate some aspects to make the skills more intuitive for the LLM.

Experiments - Full Runs

We started evaluating NetPlay by letting it play NetHack without any constraints and tasking it to win the game. We refer to this agent as the unguided agent. We conducted 20 runs with the unguided agent. Additionally, we performed 100 runs, each with autoascend

| Metric | unguided agent | guided agent | autoascend | handcrafted |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Score | 284.85 ± 222.10 | 405.00 ± 216.38 | 11341.94 ± 11625.39 | 250.24 ± 159.17 |

| Depth | 2.60 ± 1.39 | 2.00 ± 1.05 | 4.01 ± 3.04 | 2.35 ± 0.93 |

| Level | 2.40 ± 1.23 | 3.30 ± 0.95 | 3.34 ± 7.69 | 2.39 ± 1.05 |

| Time | 1292.10 ± 942.74 | 2627.40 ± 1545.12 | 21169.81 ± 9155.59 | 1306 ± 924.17 |

The results show that autoascend far outperforms NetPlay. While NetPlay beat the handcrafted agent by a small margin, it is likely that with a few tweaks the handcrafted agent can also outperform NetPlay.

The unguided agent primarily failed due to timeouts, followed by deaths caused by eating rotten corpses, fighting with low health, or being overwhelmed by enemies. Many timeouts were caused by the agent attempting to move past friendly monsters, such as a shopkeeper. By default, bumping into monsters attacks them, but for passive monsters, the game prompts the player before initiating an attack. The agent’s refusal to attack these monsters often leads to a loop of canceling the prompt and moving, resulting in eventual timeouts. A similar loop took place when the agent attempted to pick up an item with a generic name on the map but a detailed name in the game’s menu. This confusion led the agent to repeatedly close and reopen the menu, unable to locate the desired item.

Based on the results of the unguided agent, we constructed a guide that included strategies from autoascend, such as staying on the first two dungeon levels until reaching experience level 8, consuming only freshly slain corpses to avoid eating rotten ones, and leveraging altars to acquire items. Furthermore, we provided tips for common mistakes by the unguided agent, such as avoiding getting stuck behind passive monsters and informing the agent about the time limit to avoid timeouts.

The guided agent often managed to stay alive longer by consuming freshly killed corpses and praying when hungry or at low health. Its causes of death have been a mixture of timeouts, starvation, and dying in combat. Most of the timeouts stemmed from a bug with our tracker, which fails to detect when an object disappears while being obscured by a monster. For example, the agent repeatedly attempted to pick up a dagger already taken by its pet due to the tracker’s misleading observation. Despite receiving game messages indicating the absence of the item, the agent failed to recognize the situation accurately.

Experiments - Scenarios

After conducting the full runs, we hypothesized that although NetPlay can be creative and interact with most mechanics in the game, it tends to fixate on the most straightforward approach for a given task. To confirm this hypothesis, we tested NetPlay in various small-scale scenarios.

Discussion

Our experiments show that despite the immense complexity of NetHack, the agent can fulfill a wide range of tasks given enough context information. To our knowledge, this is the first NetHack agent to exhibit such flexible behavior. However, the benefits of the presented approach diminish the more ambiguous a given task is, making tasks such as “Win the Game” impossible.

A promising use case of the presented architecture is regression testing during game development. Game developers could test specific aspects of their game by providing NetPlay with detailed instructions on what to test. This approach could not only streamline the testing process but also benefit from NetPlay’s flexibility, enabling the tests to adapt dynamically as the game evolves.

Given NetPlay’s proficiency when given detailed context information, an obvious extension to our approach would be granting the agent access to the NetHack Wikipedia. This could be done using a skill that accepts a query and adds the resulting information to the agent’s short-term memory. While this can improve the results at the cost of more LLM calls, finding the most relevant information for a given situation is tricky. Instead, we recommend investing future research into automated methods for finding relevant context information, with a particular focus on finding the most successful past interactions as guidelines on how to play.

A significant limitation of our approach lies in the predefined skills and observation descriptions, which struggle to encompass NetHack’s vast complexity. Designing the agent to handle all potential edge cases proved challenging, as it is difficult to anticipate every scenario. While the premise of this approach is that the LLM can handle these edge cases, this is only true as long as we have a comprehensive description of the environment and flexible skills. In practice, achieving such a well-designed agent requires an ever-growing repertoire of skills and an observation description that grows infinitely. As such, another promising research direction is to use machine learning to replace the handcrafted components of the agent.